I spent last Sunday at The National Gallery in London with my friend, Steve. Navigating the rooms of world-famous paintings isn’t easy, especially at the weekend. But, on the brink of retiring for another coffee, we found ourselves motionless and staring in puzzlement at one particular piece.

It wasn’t the biggest, nor the most famous in the room (the small matter of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers was a few along). But it hooked us. And we spent the next ten minutes talking about it – deliberately ignoring the description so we could enjoy the mystery of what might be going on.

The more we talked, the more I knew it would make a great philosophical stimulus for ages 10+.

(If you teach children younger than this, you can follow the same method below for any other intriguing picture. I’ve linked to one example at the bottom).

Step One: What’s going on?

Show the painting to your class (click the above for a larger version).

Get them talking in pairs about what they think is going on.

What questions might they need to ask to understand it better?

Teachers notes: It’s called “An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump” by Joseph Wright, from 1768. A lecturer is demonstrating the creation of a vacuum to a family. A cockatoo is imprisoned in a glass flask, from which air is being extracted. The painting shows a range of reactions from the onlookers – from curiosity to distress. The lecturer stares outwards, inviting us viewers to make up our own minds.

You can either get them to research the answers to their questions themselves, or act as a human-Google yourself, using the notes and if you wish, further background here.

Step Two: What philosophical questions can we make?

Emotionally-charged and multi-layered stimuli like this are rich with concepts, so as you and the your class discuss the painting, keep a note of these on the board. You might come up:

- Modernity

- Progress

- Animals

- Experimentation

- Responsibility

Challenge students to think of questions that, unlike the last round, aren’t ones we can Google and find out, but instead – ones we can argue about.

They might begin with words like Does / Is / Are / Should / Can / When… Here’s a few to have up your sleeve:

- Should animals be used to help advance science? If so, when? How?

- Is all progress good?

- Do we have a responsibility to protect all life?

- Is there anything scientists shouldn’t research?

- What are the responsibilities of a scientist?

You could talk for just as long about the details of the painting alone. For example, the boy by the window – is he lowering the cage to put the bird safely back in, or raising it back to where it was?

I road-tested this with students in our online classes yesterday and the hour whizzed by. I hope you enjoy whatever discussions ensue from a piece that has so many hallmarks of a good stimulus – intrigue, tension and plenty of underlying concepts. Learn more about choosing stimuli with Jason’s article “Finding the Fence“.

For younger children

Here’s another one that can be used for younger children. It’s a still taken from an animation based on Alexis Deacon’s book Beegu. In the story, an alien who crashlands on Earth and struggles to make friends. You can use the still as the stimulus – following the method above – and use the whole animation as a way to explain the background before generating philosophical questions. Thanks to DialogueWorks for highlighting the philosophical potential of this one.

Reminder – last chance to buy!

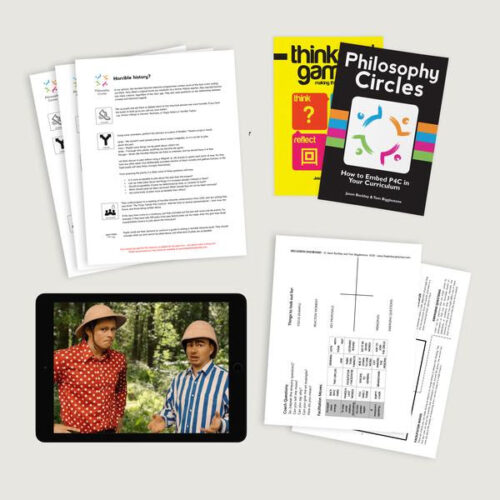

We’re excited to soon announce a new collaborative chapter for us, which will help schools access our resources through a subscription. So we’ll be removing our Curriculum Resource Pack from our shop – so this is your last chance to buy (with 20% off thrown in)! You get over 200 session plans, books, EYFS resources and more!

The pack will be available in our shop until Thursday April 4th.

Best wishes,

Tom