The Sum of Human Happiness?

I’m going to give you a bowl of ice cream. Your favourite flavour, served just how you like it in the ideal portion size. As it’s an imaginary bowl of ice cream, add whatever toppings you like. It’s on the house. I’m also throwing in a warm summer’s day so that it will be cool and refreshing.

Sounds good? There’s a catch. In this thought experiment, there is no gain without pain. For obscure reasons, to receive your bowl of delicious, pleasurable ice cream, you also have to submit to some sort of pain. Which of the following would you be willing to endure in exchange for your ice cream?

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds?

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds, but using a pair of pliers?

Be pinched on the arm (the pliers are gone, you’ll be pleased to hear, back to finger and thumb) for 1 minute? 10 minutes?

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds, but with only a 50/50 chance of getting the ice cream?

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds now, but you get the ice cream in a week? In a year?

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds, knowing it will leave a very slight ache for the rest of the day (assume I have an excellent pinching technique)?

Be pinched on the arm, get the ice cream, but know that the ice cream will also give you a tummy ache (that’s the problem of natural evil, which is for another time)?

The chances are that you said yes to some of these, but not to others. What you’ve been doing is using “the prudential calculus” – weighing up pleasures and pains and seeing whether overall, there’s more benefit in each ice-cream/pinching combination than in leaving your appetite unsatisfied and your arm unpinched.

Prudence is about weighing up different parts of your life and taking decisions that make sense in your life overall. For example, you might study hard in a subject you don’t much enjoy, because you know it will be important to pass the exam at the end of it. Or, much as I might enjoy it, I might not drink the bottle of champagne sitting in the fridge because I don’t want a hangover in the morning. It’s about your present self being kind to your future self, and perhaps making a sacrifice now so that your future self can be better off.

You might also be kind to other people and make sacrifices for them. I might share my bottle of champagne because someone else would enjoy it. You might study hard for your exams because you want to train to be a doctor and help other people. That’s a different sort of calculation, but it still involves weighing up pleasures and pains and seeing what is going to lead to the best balance of pleasure over pain in all the people involved.

One way of putting this is that doing the right thing is about promoting “the greatest happiness of the greatest number”. One person who thought this way was Jeremy Bentham. He lived from 1747 to 1832 and then, as directed in his will, he was mummified so that he could join his friends for dinner if they missed him. Presumably, he thought the pleasure of seeing their old friend would outweigh the pain of being put off their food.

Bentham wrote a poem about the things you should bear in mind when adding up pleasures and pains.

Intense, long, certain, speedy, fruitful, pure—

Such marks in pleasures and in pains endure.

Such pleasures seek if private be thy end:

If it be public, wide let them extend

Such pains avoid, whichever be thy view:

If pains must come, let them extend to few.

He was a better philosopher than he was a poet, but it’s a handy rhyme. The questions I asked you at the start connect to each of these:

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds?

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds, but using a pair of pliers? (intense)

Be pinched on the arm (the pliers are gone, you’ll be pleased to hear, back to finger and thumb) for 1 minute? 10 minutes? (long)

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds, but with only a 50/50 chance of getting the ice cream? (not certain)

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds now, but you get the ice cream in a week? In a year? (not speedy)

Be pinched on the arm for ten seconds, knowing it will leave a very slight ache for the rest of the day (assume I have an excellent pinching technique)? (fruitful – pains that lead to more pains, or pleasures that lead to more pleasures)

Be pinched on the arm, get the ice cream, but know that the ice cream will also give you a tummy ache (not pure – is it all pleasure, or is it mixed with pain)

To those scenarios, we could add:

You get the ice cream, and so do five other people. Only you get pinched. (let pleasures extend to as many people as possible)

Only you get the ice cream. Five other people get pinched. (let pains extend to as few as possible)

Do you agree that right and wrong is about weighing up the results of your actions and seeing if they lead to greater happiness overall? That way of looking at ethics is a type of consequentialism – a philosophy that judges actions by their consequences rather than by whether they follow particular rules. See what you think about this situation.

Goodbye, Mr Fish

Mr Fish is a schoolteacher approaching retirement. He is very keen on consequentialism. So he decides on his last day at school to do one final thing to help create the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

He plays a prank on the headteacher, perching a bucket of flour above the door through which the headmaster walks on stage at the beginning of assembly. Just as he expects, the five hundred children in the hall roar with laughter and are absolutely delighted. The headmaster is a bit shocked and humiliated, but soon recovers.

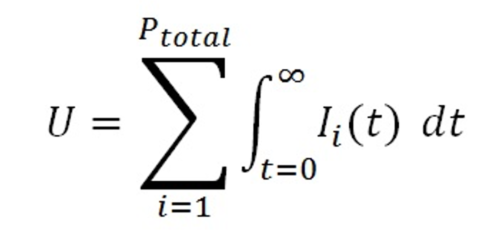

Mr Fish reasons that even though the headmaster is made more unhappy than any one of the children watching, when you add up the small increase in the happiness of every child that sees the prank, it outweighs the headmaster’s suffering with lots to spare. He takes account of all the later consequences – the headmaster being cross for the rest of the day, the probability of some of the pupils trying the prank at home, and so on, and concludes that overall he is promoting the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

Let’s assume he is right, and that there really is more happiness overall as a result of his prank. Has he done a good thing?

I’ll say again, let’s assume he is right about it creating more happiness. We are doing philosophy. We are not deciding whether to pour flour over a headmaster (at least I hope not) so the practical side of things doesn’t matter. If you like, I can Mr Fish a maths teacher so that he is very good at such calculations. I can make the pupils’ lives extremely boring, so that this will be the best fun they have had in years. I’ve made them all up, so trust me, there is definitely more happiness in this imaginary world after the prank than before.

What I’m asking is if that is enough to make what Mr Fish does a good thing to do? Is he being a good person in playing the prank? Or are there other things about right and wrong that are invisible when all you are looking for are the pleasures and pains caused by an action?

Miss Salt and the Happy Spiteful Brats

Here’s another scenario. Inspired by Mr Fish, Miss Salt decides to increase the happiness of her English class, 8U2. 8U2 are a horrible group of spiteful brats, with the exception of Persimmon Bigglestone. He is a pleasant young man who is hardworking and bright, always comes top in tests and takes pride in his work without being a show-off.

In this rather old-fashioned school, after a test they read out the results, starting with the person who came top and working down to the lowest score. Miss Salt realises that if she plays a trick on Persimmon, and makes out that he has scored the worst in the class, the combined delight that the brats in her class will feel at his discomfort will be far greater than Persimmon’s temporary shock.

Again, as I’ve made them all up, please trust me that overall happiness will be increased by Miss Salt’s joke. If I was a psychologist, I might be more concerned about the long-term scars on Persimmon’s psyche, and if I were from OFSTED I might question Miss Salt’s approach to assessment and feedback. But what we are interested in is IF the overall happiness is increased THEN has Miss Salt done a good thing? Is that what doing a good thing means, or is there more (or less) to doing good than increasing happiness?