Do you want to do P4C but struggle to fit it on the timetable?

You know enough about P4C to think it would be good for your school. But there are obstacles to implementing it. The traditional way of doing P4C, in stand-alone sessions of around one hour, doesn’t fit in your timetable. Teaching staff, already under pressure, are wary of taking on “yet another thing”, and don’t feel they are ready to plan what to do and know that they are “doing it right”. So how can you support colleagues to make P4C work with your existing curriculum?

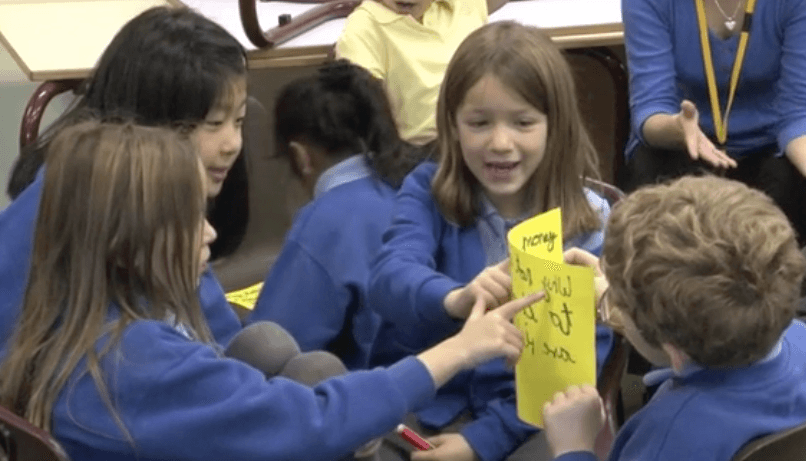

Help children find their voices

More and more children arrive in reception scarcely talking at all

Parents distracted by social media speak less to their children. In one school with a high proportion of younger parents, the number of children arriving completely nonverbal rose from five to half the class in just five years.

If they don’t learn to talk confidently to groups in their primary years, it’s unlikely they ever will. That impacts their learning, and their economic and social wellbeing. You'll learn how to overcome the different obstacles children have to speaking, and get (almost) every child talking.

- Playground Confident, Classroom Shy – how to empower children who clam up in the classroom to speak

- Feed Forward: a simple change to give speech-poor children time to catch up

- Chance, Chain, Choose – how to reduce inequality in the classroom

- Separating Thinking and Speaking – how to beat the “I dunno” card

- Unwrongification – how to free children from the fear of getting it wrong

- Small Talk Big Talk - how to keep them talking while raising the stakes

Children speak best when they are standing up

They don't go to dinner parties or sit around in the pub. The Get Moving activities explained in this course get (almost) every child talking from the first minute of a session. Learn how this high-energy approach works, so that you can increase the engagement of all your learners not just in philosophy but across your teaching.

- How to make thinking a game by making it physical

- Community builder activities to help your class collaborate

- How philosophical playfulness leads to “deep fun”

- How to create shared experiences that stimulate thinking

- Argumentag and other debate games that build confidence

Y-Questions that stretch but don’t scare

Less confident speakers can fear speaking in class because they are worried about getting it wrong. That freezes the development of their speaking while other, more confident children do the talking and speed ahead. The Y-Questions at the heart of Philosophy Circles present clear, difficult-to-decide choices, allowing less confident learners to feel they won’t get it wrong while giving a greater challenge to able children who are used to getting it right.

In the course and supporting resources, you'll learn:

- Why closed questions can be better than open ones

- How to find stimuli that encourage thinking, but don't say what to think

- How Philosophy in Role in your topics engages children's imaginations

- How children can create their own Y-Questions – and when to use your own

- How children can tell stories that enrich their thinking and their writing

What do teachers say?

"It has been fascinating to watch the children engage with a range of challenging topics with maturity, enthusiasm and empathy thanks to the facilitation provided by Tom. Their curiosity was inspired by the thought-provoking stimuli in each session and several individuals, who usually find it challenging to share their ideas, came to the fore during the big discussions.

Pupils comment that they are thoroughly enjoying P4C and enthusiastically anticipate their lessons with Tom each week; they also site that ‘they enjoy the challenges to their thinking.’

Since commencing P4C, we have noticed a dramatic increase in the children’s ability to discuss concepts with their peers and they have vastly improved in their ability in looking at one another when speaking, in actively listening to one another and in building upon and challenging others’ views and opinions. Before the lessons started, the children were not listening deeply to one another and responding to one another constructively – they had their opinion and that was it. We have also noticed an increase in confidence and concentration.

Initially, the children tended to direct their responses towards the adult. After a couple of weeks however, they were looking at the child they were responding to and dialogue bounced around the room without adult intervention

The children’s critical reasoning skills were also developed; children were starting to support their views with reasons.

Enquiry based methods are also being instigated by the pupils themselves in other curriculum areas:

Who is the villain in Macbeth?

Who is responsible for King Duncan’s death?

Was the Highwayman guilty of any crime?

Is jealousy an acceptable motive for murder?

Can murder ever be justified?

As teachers, we are excited about working elements of P4C into our day-to-day classroom practice, particularly when creating and discussing questions during class reading sessions."

Shareen Johnson

Amesbury Primary School

absorb

absorb